At the beginning of 2026, capital gains tax (CGT) reform has once again found its way into public discussion, with speculation growing that potential changes could be announced in the upcoming federal budget. As with any tax-related headlines, this has prompted understandable questions from investors:

– Will this change the property market?

– Should I act differently?

– Does this alter my long-term strategy?

These are rational questions. Tax settings matter, but reacting to headlines and understanding structural impact are two very different things.

The 50% CGT Discount Did Matter

It’s important to acknowledge upfront that the introduction of the 50% CGT discount in 1999 was a meaningful structural shift.

Moving from indexation to a flat 50% discount for assets held longer than 12 months materially improved after-tax returns. It strengthened the appeal of leveraged growth assets and supported capital growth-focused strategies.

Over the past two decades, that framework has been embedded into investor behaviour.

However, there is an important distinction between introducing a structural incentive (as occurred in 1999) and adjusting an established system in a mature market already shaped by that incentive.

That nuance matters when assessing potential reform today.

Behavioural Shifts vs. Structural Drivers

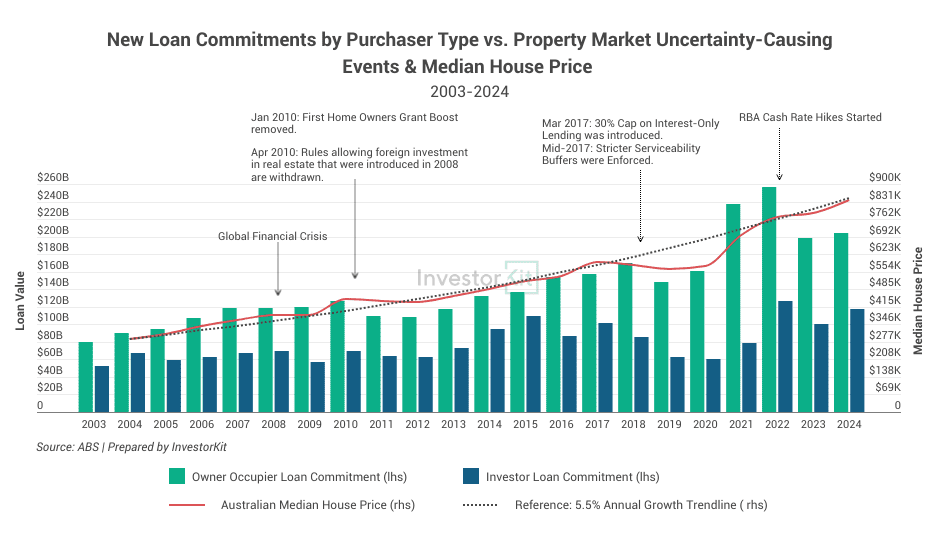

If CGT reform is introduced today, for example, by reducing the discount, the most immediate impact would likely be on the behaviour of investors who rely heavily on shorter holding periods (but still longer than 12 months) or who prioritise capital gains as their primary outcome. Transaction volumes could temporarily reduce in the same manner whenever uncertainty arises (as shown in the chart below).

But that doesn’t automatically translate to structural market declines.

Why? Because long-term property performance is primarily driven by structural forces such as:

- Population growth and household formation

- Housing supply constraints

- Credit availability and borrowing capacity

- Employment and wage growth

- Infrastructure investment and amenity

CGT reform does not alter the underlying imbalance between supply and demand.

Owner-Occupiers Still Anchor the Market

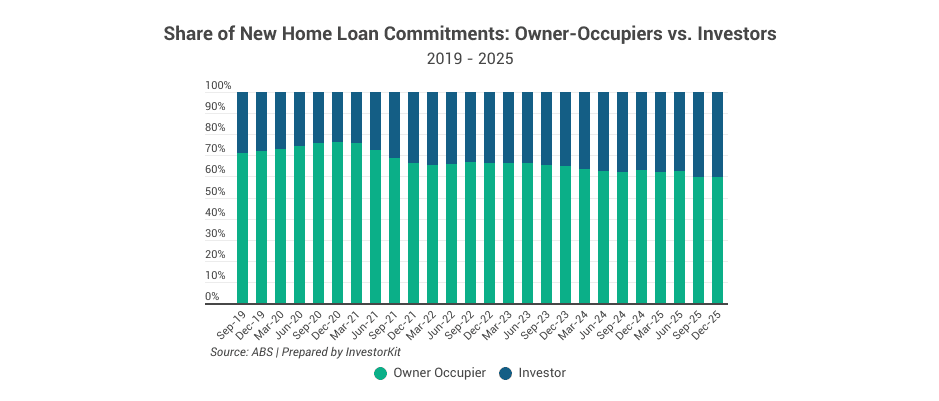

Another critical factor is market composition.

Around 60% of new housing loan commitments currently come from owner-occupiers (see chart below), who are generally exempt from CGT on their principal place of residence. Their decisions are driven by lifestyle needs, employment, affordability and borrowing capacity, not capital gains tax policy.

This acts as a stabilising force.

Even if investor sentiment softens temporarily, owner-occupier demand remains largely intact. Historically, that has limited broad-based price impacts from investor-specific policy changes.

The Liquidity Effect: An Often Overlooked Outcome

There is, however, a more subtle channel through which CGT reform could influence the market: liquidity.

If selling becomes less tax-efficient, some investors may choose to hold assets longer to avoid high taxes. This isn’t just theoretical. Empirical studies globally tend to show that lower capital gains tax rates increase transaction volumes, while higher tax rates reduce turnover. That’s a phenomenon known as the “lock-in effect”.

In simple terms, when the cost of selling rises, fewer people sell.

In markets already experiencing low listing volumes, reduced turnover can further tighten the supply of established stock and intensify competition for quality assets, which could even push price up if demand remains high.

This is why policy designed to dampen investor incentives does not automatically translate into downward price pressure.

Reform Is Likely to Be Measured

Implementation is also worth considering.

Capital gains tax applies across multiple asset classes, including property, shares and business assets. Because of its broad reach, governments historically approach reform cautiously.

Changes are typically implemented with transitional arrangements or grandfathering provisions to avoid abrupt disruption.

While public debate may feel urgent, structural tax shifts tend to be measured and far less destabilising.

Strategy Over Reaction

For sophisticated investors building long-term portfolios, the takeaway is simple:

Tax should inform strategy, but it should not become the strategy.

The 50% discount improved the attractiveness of growth assets. That’s true. But high-performing portfolios have never relied solely on tax settings.

They rely on:

- Buying scarce assets

- Targeting markets with strong fundamentals (demand, supply, sentiment, etc.)

- Managing risk through disciplined due diligence

- Building the portfolio with a long-term sustainability perspective

Chasing tax advantages while overlooking asset quality has historically led to underperformance.

Every investor’s position is different. If reform proceeds, its impact will depend on your income structure, portfolio mix, borrowing capacity and long-term goals.

The key is not reacting to policy noise, but understanding how it fits within a clear, data-driven strategy.

If you’d like clarity on how potential CGT reform could affect your portfolio, whether that’s timing decisions, structuring your next acquisition, or mapping out your long-term plan, book a free 15-minute Discovery Call with our team.

Let us help you cut through the noise and assess your position strategically, so your portfolio continues to work as hard as you do.

The right strategy, executed well, will always outperform uncertainty.

.svg)